During the years 2011 through 2014, an estimated 29,000 women with HCV infection gave birth each year in the United States, with an estimated 6% of these births resulting in HCV transmission.[1] Thus, during these years, approximately 1,700 new perinatal HCV infections occurred annually.[1,2] Between 2016 and 2021, the number of pregnant women with HCV infection ranged from a low of 16,588 in 2016 to a high of 18,927 in 2018.[3] (Figure 1) In the United States in 2021, there were 16,923 births to mothers with HCV infection and the rate of maternal HCV was highest among women 25 to 29 years of age.[3] The total number of pregnant women with HCV was highest in White women, but the rate was highest in American Indian/Alaska Native women.[3] In 2021, there were 199 cases of perinatal HCV reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[4] Although perinatal HCV infection has been a notifiable condition since 2018, these 199 cases are likely a gross underestimate of the total number of perinatal HCV cases in 2021. Despite the significant number of perinatal HCV transmissions that occur in the United States, screening for HCV during pregnancy has historically been inconsistent and use of HCV risk-based screening has been shown to underestimate the true prevalence of HCV among pregnant women.[5,6]

- Module 6 Overview

Treatment of Key Populations and Unique Situations - 0%Lesson 1

Treatment of HCV in Persons with HIV CoinfectionActivities- 0%Lesson 2

Treatment of HCV in Persons with Renal ImpairmentActivities- 0%Lesson 3

Treatment of HCV in Persons with Substance UseActivities- 0%Lesson 4

Treatment of HCV in a Correctional SettingActivities- 0%Lesson 5

Management of Health Care Personnel Exposed to HCVActivities- 0%Lesson 6

Perinatal HCV TransmissionActivitiesLesson 6. Perinatal HCV Transmission

PDF ShareLast Updated: January 10th, 2025Author:Maria A. Corcorran, MD, MPHMaria A. Corcorran, MD, MPH

Associate Editor

Assistant Professor

Division of Allergy & Infectious Diseases

University of WashingtonDisclosures: NoneReviewer:David H. Spach, MDDavid H. Spach, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Professor of Medicine

Division of Allergy & Infectious Diseases

University of WashingtonDisclosures: NoneLearning Objective Performance Indicators

- Describe the current guidelines for HCV screening in pregnant women

- Identify the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HCV and factors associated with increased risk of transmission

- Summarize the impact of HCV on pregnancy outcomes

- Describe interventions and/or prophylactic measures to reduce the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HCV

- List recommendations for HCV testing and management in infants born to mothers with HCV.

Table of Contents- Perinatal HCV Transmission

- Background

- HCV Screening During Pregnancy

- Factors Associated with HCV Perinatal Transmission

- Impact of Chronic HCV Infection on Pregnancy

- Effect of Pregnancy on Chronic HCV

- Interventions to Prevent Mother-to-Child Transmission of HCV

- Safety of HCV Treatment During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

- Monitoring of Pregnant Women with HCV

- Management of Infants and Children Born to Mothers with HCV Infection

- Summary Points

- Citations

- Additional References

- Figures

Background

HCV Screening During Pregnancy

Recommendations for HCV Screening During Pregnancy

In the setting of increasing HCV prevalence among women of reproductive age and emerging data supporting the cost-effectiveness of universal screening for HCV during pregnancy, routine HCV screening is now recommended by multiple agencies for all pregnant women in the United States, as outlined below.[7,8]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Routine HCV screening is recommended for all pregnant women during each pregnancy, except for in settings where the prevalence of HCV RNA positivity is less than 0.1% (a condition not currently met by any state in the United States).[8,9,10]

- United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF): The USPSTF recommends screening for HCV in adults aged 18 to 79 years, including pregnant women.[11]

- American Association for the Study of the Liver Diseases/Infectious Diseases Society of America (AASLD/IDSA): As part of prenatal care, all pregnant women should be tested for HCV infection with each pregnancy, ideally at the initial visit.[12]

Recommended HCV Screening Method in Pregnancy

Screening should be done through the serologic detection of antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV), followed by a nucleic acid test (NAT) for HCV RNA in patients with a positive anti-HCV screen.[8] Although an optimal time for HCV screening during pregnancy has not been identified, screening is often done at an early prenatal visit along with screening for other infectious diseases, such as HIV and hepatitis B virus (HBV). If a pregnant woman screens negative for HCV early on in pregnancy but has ongoing risk factors for HCV, a follow-up test can be considered later in pregnancy.[8]

Factors Associated with HCV Perinatal Transmission

Perinatal, or mother-to-child, transmission of HCV is confined to women who have an active HCV infection, defined by detectable HCV RNA, during pregnancy.[13,14,15,16,17] Among HCV viremic women, perinatal transmission occurs in approximately 6 to 7% of pregnancies.[4,18,19,20,21] The mechanism and timing of perinatal transmission are poorly understood, but most infections are thought to be acquired in utero, with one study estimating that 24.8% of perinatal infections occurred early in utero, 66% late in utero, and 9.3% at the time of delivery.[21,22,23,24] In a study involving 54 children enrolled in the European Paediatric Hepatitis C Network, investigators found that 31% of children were HCV RNA positive within 3 days of birth, suggesting evidence of intrauterine transmission, while 50% of infants were HCV RNA negative at 3 days and subsequently positive at 3 months, suggesting late intrauterine or intrapartum transmission.[24] As outlined below, multiple factors have been examined that potentially correlate with increased risk for perinatal HCV transmission among mothers with HCV RNA-positive infection during pregnancy.

- Maternal HCV RNA Levels: In general, studies suggest that a higher maternal HCV viral load correlates with increased risk of perinatal transmission, but a precise viral threshold conferring increased risk of mother-to-child HCV transmission has not been identified.[15,25,26,27]

- Coinfection with HIV: Several studies have shown that women with HCV viremia and coinfection with HIV have an increased risk of perinatal HCV transmission.[20,28,29,30] In a meta-analysis of 25 studies, the estimated rate of perinatal transmission was 5.8% among HCV viremic women without HIV coinfection and 10.8% among HCV viremic women with HIV coinfection.[20] In an updated analysis of 1,749 children from 3 prospective European cohorts, authors estimated the rate of HCV vertical transmission to be 7.2% in mothers with HCV monoinfection, compared to 12.1% in mothers with HCV and HIV coinfection.[21] The mechanism whereby HIV increases the risk of perinatal HCV transmission is not fully understood but may relate to HIV-related increases in HCV RNA levels.[31]

- Maternal Injection Drug Use: Several studies have shown that maternal injection drug use significantly increases the risk of perinatal HCV transmission.[17,32] The mechanism for this enhanced risk is not clearly known, but may result from the increased infection of peripheral blood mononuclear cells with HCV that occurs among persons who inject drugs, or superinfection with additional HCV variants during pregnancy.[32]

- Intrapartum Exchange of Fluids: Several factors have been identified that enhance the risk for perinatal HCV transmission at the time of delivery, including prolonged rupture of membranes (longer than 6 hours) and obstetric procedures (and intrapartum events) that result in infant exposure to maternal blood, such as internal fetal monitoring or vaginal/perineal lacerations.[26,33] In contrast, mother-to-child HCV transmission has not been associated with the mode of delivery (e.g., vaginal versus cesarean].[18,33]

- Breastfeeding: Although HCV RNA is detectable in colostrum, data from large cohorts of mothers with HCV infection and their exposed infants have demonstrated that breastfeeding does not increase the risk of HCV transmission from mothers to their babies, provided the mother’s nipples are not cracked or bleeding.[26,32,34]

Impact of Chronic HCV Infection on Pregnancy

Impact of HCV on Pregnancy Outcomes

There are several studies linking maternal HCV infection with worse pregnancy outcomes, including higher rates of gestational diabetes, fetal death, preterm delivery, low birth weight, small for gestational age, antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage, and premature rupture of membranes.[27,35,36,37,38,39] Data clearly demonstrate that women with cirrhosis are at risk for worse maternal and neonatal outcomes.[40,41] In contrast, the association between HCV infection (without cirrhosis) and pregnancy outcomes is less clear due to common potential confounders, such as socioeconomic status and substance use.[40,41] Nonetheless, a meta-analysis of nine studies evaluating the association between maternal HCV and preterm birth found that preterm births were 62% more likely among mothers with HCV infection, an association that held true when stratified by maternal smoking, alcohol use, drug use, and coinfection with HBV and/or HIV.[37] Similarly, in a prospective observational study of 342 HCV antibody-positive pregnant women in Egypt, none of whom had a history of injection drug use, authors found that women with HCV had higher rates of antepartum hemorrhage, postpartum hemorrhage, anemia, gestational diabetes, premature rupture of membranes, and admission to an intensive care unit when compared to 170 control women.[35]

HCV and Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy

There is strong evidence linking chronic HCV to increased rates of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. In a retrospective review of 91 pregnant women with HCV, investigators from Marshall University found that 45% (41 of 91) of women were diagnosed with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.[42] In this study, women with HCV and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy had significantly higher median HCV RNA levels when compared to those without intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (495,000 copies/mL versus 8,000 copies/mL).[42] Similar findings were shown in a systematic review and meta-analysis that included three studies: women with chronic HCV had 20-fold higher odds of developing intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy than women without HCV.[43] Given the significantly increased risk of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy among women with HCV, clinicians caring for pregnant women with HCV infection should be aware of this association, since early recognition and appropriate therapy can improve fetal outcomes.

Effect of Pregnancy on Chronic HCV

Although conflicting reports exist on the effect of pregnancy on liver disease in women with chronic HCV, it is generally believed that pregnancy has minimal impact on HCV-related progression of fibrosis.[44,45] Nevertheless, HCV has been associated with elevated alanine aminotransferase levels (ALT) levels in pregnancy, with one Italian cohort of 370 anti-HCV-positive reporting 56.4% of study participants experienced elevated ALT levels in the first month of pregnancy, 7.4% in the last trimester, and 54.5% in the postpartum period.[46] Other studies have suggested a decline in HCV RNA postpartum, with an estimated 10% of women experiencing spontaneous clearance of HCV after childbirth.[47,48,49] Because of these findings, pregnant HCV RNA-positive women should have HCV RNA testing performed 9 to 12 months after giving birth to assess for possible spontaneous HCV clearance.

Interventions to Prevent Mother-to-Child Transmission of HCV

There are no interventions or prophylactic measures that have been proven to prevent perinatal transmission of HCV. The following summarizes key issues and recommendations regarding preventing HCV perinatal transmission.

- Direct-Acting Antiviral (DAA) Therapy in Pregnancy: Although there are no large-scale clinical trials evaluating the impact of DAA therapy on mother-to-child transmission of HCV, evaluating the impact of DAA therapy on mother-to-child transmission of HCV, but , a series of small studies suggest that sofosbuvir-based DAAs are likely safe and effective during pregnancy.[50,51] In a phase 1 trial, 9 women with HCV received ledipasvir-sofosbuvir during pregnancy, and the treatment was found to be effective and safe, with 100% of participants achieving an SVR12 and no cases of perinatal transmission.[52] In a prospective observational study from India, 26 treatment-naïve pregnant women without cirrhosis were given ledipasvir-sofosbuvir after the first trimester of pregnancy and all achieved an SVR12; none of the infants had congenital malformations or detectable HCV RNA at 6 months of age.[53] In a similar, but larger, ongoing study of 50 women initiated on sofosbuvir-velpatasvir between 20 and 30 weeks’ gestation (STORC study), there have been no cases of perinatal transmission to date (n = 26), and 100% of women who have completed treatment and attended their SVR12 visits have been cured (n = 35).[54] Given the limited data on HCV treatment during pregnancy, the AASLD-IDSA HCV Guidance recommends treating women of reproductive age before pregnancy, if practical and feasible, to reduce the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HCV.[51] In addition, the AASLD-IDSA HCV Guidance states that treatment during pregnancy can be considered on an individual basis after shared decision-making.[51]

- Invasive Monitoring During Gestation: If invasive monitoring is needed during pregnancy, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommends amniocentesis, with avoidance of placental contact, over chorionic villus sampling, as amniocentesis has not been linked with increased rates of mother-to-child transmission of HCV.[27,51]

- Intrapartum Procedures and Monitoring: Prolonged rupture of membranes (longer than 6 hours), obstetric procedures, and intrapartum events that lead to infant exposure to HCV-infected maternal blood, such as internal fetal monitoring or vaginal/perineal lacerations, should also be avoided to reduce the risk of perinatal transmission.[2,26,32,33]

- Mode of Delivery: There are no data to suggest cesarean section reduces the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HCV compared with vaginal delivery, and as such, routine use of cesarean section to prevent perinatal HCV transmission is not recommended.[18,33]

Safety of HCV Treatment During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents

Although there are limited data on the safety and efficacy of using DAAs to treat HCV during pregnancy and/or lactation, available small-scale studies suggest that treatment with sofosbuvir-based DAAs (e.g., ledipasvir-sofosbuvir or sofosbuvir-velpatasvir) is likely safe during pregnancy; there is very limited to no data on the use of glecaprevir-pibrentasvir during pregnancy. In animal studies, it appears that all commonly used DAA regimens cross the placenta and transfer into breast milk.[55] However, no adverse safety signals in animal studies have been identified, and limited available data on the use of DAAs in humans during pregnancy suggest no increase in congenital abnormalities or complications.[27,52,53,54,55] In an ongoing study evaluating the safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir in 50 pregnant women, gastrointestinal side effects, including nausea, vomiting, and GERD, have been common; there have been no reports of cholestasis, no related serious adverse events in either the mother or baby, and no observed increase in rates of preterm birth (when compared to persons with HCV who are not receiving DAA treatment).[54] In addition, a small phase 1 study evaluating ledipasvir-sofosbuvir in 8 pregnant women showed no safety concerns.[52] Emerging clinical practice data is similarly reassuring, with no fetal anomalies reported across several studies of pregnant women exposed to DAAs, including in the Treatment in Pregnancy for Hepatitis C (TiP-HepC) Registry, where clinicians report outcomes of maternal-infant pairs exposed to DAAs during pregnancy.[56] Despite these preliminary findings, further data on the safety and efficacy of DAAs to treat HCV during pregnancy are needed.[51]

Ribavirin

Although infrequently used in the current DAA era, ribavirin is absolutely contraindicated during pregnancy due to known teratogenic effects. Women exposed to ribavirin and female partners of men taking ribavirin should delay pregnancy for at least 6 months following ribavirin exposure, given the persistent risk of teratogenicity related to ribavirin.[51] Ribavirin has not been adequately studied in nursing mothers.

Monitoring of Pregnant Women with HCV

Monitoring During Pregnancy

Since routine anti-HCV screening is recommended during each pregnancy, some women will have an initial diagnosis of HCV while pregnant. For those women who newly screen anti-HCV positive, it is important to obtain a quantitative HCV RNA level (if not already done) and routine liver function tests to assess the risk of mother-to-child transmission and severity of liver disease.[51] The initial evaluation of women with HCV infection diagnosed during pregnancy is generally similar to the initial evaluation of nonpregnant women diagnosed with HCV (see Module 2 Initial Evaluation of Persons with Chronic Hepatitis C). In addition, a pregnant woman with HCV should have fibrosis staging if not previously done (see Module 2 Evaluation and Staging Monitoring of Liver Fibrosis). Given the elevated risk of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, women with HCV infection who develop pruritus or jaundice during pregnancy should undergo subsequent assessment of liver function testing to evaluate for this pathologic process.[51]

Monitoring in the Postpartum Period

Although HCV RNA levels tend to rise during pregnancy, they can drop substantially during the postpartum period.[50,51] This fluctuation in HCV RNA levels during pregnancy likely reflects the relatively immunosuppressed state of pregnancy, followed by immune reconstitution that occurs during the postpartum period.[27,50] The documented decline in HCV RNA levels in the postpartum period has also been associated with spontaneous clearance of HCV, and as such, HCV RNA-positive women should have repeat HCV RNA testing performed at 9 to 12 months postpartum to assess the possibility of spontaneous clearance, which occurs in approximately 10% of postpartum women.[51]

Management of Infants and Children Born to Mothers with HCV Infection

All infants born to mothers with HCV should have follow-up HCV testing, but data from two large United States-based cohorts indicate that follow-up HCV testing for infants born to mothers with HCV often does not occur.[57,58] There are several considerations when testing infants for HCV early in life: (1) passive transfer of anti-HCV from mother to child can persist for up to 18 months (Figure 3), (2) transient infant viremia can occur in the first months of life, and (3) children who perinatally acquire HCV can spontaneously clear HCV infection.[59,60,61]

Recommendations for Infant HCV Testing

To identify children in whom chronic HCV might develop and link them to care, the 2023 CDC Recommendations for Hepatitis C Testing Among Perinatally Exposed Infants and Children states that all infants and children who were perinatally exposed to HCV should be tested for HCV.[4] In these recommendations, the CDC defines perinatally exposed infants and children as those born to pregnant women with current HCV infection (positive HCV RNA during pregnancy) or probable HCV infection (reactive anti-HCV testing with no available HCV RNA results).[4] Testing perinatally exposed infants and children early in life streamlines HCV testing recommendations with standard schedules for well-child visits and limits the number of infants and children who are lost to follow-up.[4] Furthermore, through increased detection of perinatally acquired HCV infection, more children can be offered curative treatment, which is approved starting at age 3 years.[4]The following summarizes these CDC recommendations for HCV perinatally exposed infants and children (Figure 4).[4]

- Perform HCV RNA testing at 2–6 months of age (this is the preferred window for testing).

- Infants and children with a positive HCV RNA test should be managed in consultation with a health care provider experienced in pediatric HCV management.

- Infants and children with an undetectable HCV RNA do not have a current HCV infection and do not require further testing.

- Infants and children 7–17 months of age who were not previously tested should undergo HCV RNA testing.

- Children 18 months of age and older who were not previously tested should undergo hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV) testing with reflexive HCV RNA for those with a positive antibody test.

Summary Points

- The prevalence of chronic HCV is increasing among women of reproductive age.

- Routine HCV screening is recommended for all pregnant women and during each pregnancy, regardless of risk factors.

- Among HCV viremic women, perinatal transmission occurs in approximately 6 to 7% of pregnancies.

- Increased risk of perinatal HCV transmission has been associated with higher maternal HCV viral loads, maternal injection drug use, HIV coinfection, prolonged rupture of membranes, and obstetric procedures and intrapartum events that lead to infant exposure to maternal blood, such as internal fetal monitoring or vaginal/perineal lacerations.

- Mother-to-child transmission of HCV has not been associated with mode of delivery (e.g., vaginal vs. cesarean), and there is no indication to pursue elective cesarean section based solely on a woman’s HCV status.

- Breastfeeding is safe for mothers with HCV infection as long as they do not have damaged, cracked, or bleeding nipples.

- Several studies have linked maternal HCV infection with worse pregnancy outcomes, including higher rates of fetal death, preterm delivery, low birth weight, small for gestational age, antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage, gestational diabetes and premature rupture of membranes.

- Studies have shown a decline in HCV RNA postpartum, with an estimated 10% of women experiencing spontaneous clearance of HCV after childbirth. Women should have HCV RNA testing performed at 9 to 12 months postpartum to assess for the possibility of spontaneous HCV clearance.

- Use of DAA therapy has not been sufficiently studied during pregnancy, and there are no large-scale clinical trials on the safety and efficacy for treatment of women during pregnancy or breastfeeding. More recently, small-scale studies suggest that DAAs are likely to be safe and effective during pregnancy. As such, the AASLD-IDSA Guidance states that HCV treatment can be considered on an individualized case-by-case basis during pregnancy.

- The initial evaluation of women diagnosed with HCV during pregnancy is generally similar to that of nonpregnant women diagnosed with HCV and should include an HCV RNA level and fibrosis staging.

- All children born to women with HCV infection should have HCV RNA testing performed between 2 and 6 months of age. Infants and children with a positive HCV RNA test should be linked to care and managed in consultation with a health care provider experienced in pediatric HCV management. Treatment of HCV in children is approved starting at age 3 years.

Citations

- 1.Ly KN, Jiles RB, Teshale EH, Foster MA, Pesano RL, Holmberg SD. Hepatitis C Virus Infection Among Reproductive-Aged Women and Children in the United States, 2006 to 2014. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:775-782.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 2.Schillie SF, Canary L, Koneru A, et al. Hepatitis C Virus in Women of Childbearing Age, Pregnant Women, and Children. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:633-41.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 3.Ely DM, Gregory ECW. Trends and Characteristics in Maternal Hepatitis C Virus Infection Rates During Pregnancy: United States, 2016–2021. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2023:72(3).[CDC Stacks] -

- 4.Panagiotakopoulos L, Sandul AL, Conners EE, Foster MA, Nelson NP, Wester C. CDC Recommendations for Hepatitis C Testing Among Perinatally Exposed Infants and Children - United States, 2023. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2023;72:1-21.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 5.Boaz K, Fiore AE, Schrag SJ, Gonik B, Schulkin J. Screening and counseling practices reported by obstetrician-gynecologists for patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2003;11:39-44.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 6.Waruingi W, Mhanna MJ, Kumar D, Abughali N. Hepatitis C Virus universal screening versus risk based selective screening during pregnancy. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2015;8:371-8.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 7.Chaillon A, Rand EB, Reau N, Martin NK. Cost-effectiveness of Universal Hepatitis C Virus Screening of Pregnant Women in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:1888-95.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 8.Schillie S, Wester C, Osborne M, Wesolowski L, Ryerson AB. CDC Recommendations for Hepatitis C Screening Among Adults - United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-17.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 9.Rosenberg ES, Hall EW, Sullivan PS, et al. Estimation of State-Level Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection, US States and District of Columbia, 2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:1573-81.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 10.Rosenberg ES, Rosenthal EM, Hall EW, et al. Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in US States and the District of Columbia, 2013 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e186371.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 11.US Preventive Services Task Force, Owens DK, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Adolescents and Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2020;323:970-5.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 12.AASLD-IDSA. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for testing, management, and treating hepatitis C. HCV testing and linkage to care.

- 13.Dal Molin G, D'Agaro P, Ansaldi F, et al. Mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: rate of infection and assessment of viral load and IgM anti-HCV as risk factors. J Med Virol. 2002;67:137-42.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 14.Moriya T, Sasaki F, Mizui M, et al. Transmission of hepatitis C virus from mothers to infants: its frequency and risk factors revisited. Biomed Pharmacother. 1995;49:59-64.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 15.Ohto H, Terazawa S, Sasaki N, et al. Transmission of hepatitis C virus from mothers to infants. The Vertical Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:744-50.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 16.Okamoto M, Nagata I, Murakami J, et al. Prospective reevaluation of risk factors in mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus: high virus load, vaginal delivery, and negative anti-NS4 antibody. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1511-4.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 17.Resti M, Azzari C, Mannelli F, et al. Mother to child transmission of hepatitis C virus: prospective study of risk factors and timing of infection in children born to women seronegative for HIV-1. Tuscany Study Group on Hepatitis C Virus Infection. BMJ. 1998;317:437-41.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 18.Post JJ. Update on hepatitis C and implications for pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2017;10:157-160.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 19.Page CM, Hughes BL, Rhee EHJ, Kuller JA. Hepatitis C in Pregnancy: Review of Current Knowledge and Updated Recommendations for Management. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2017;72:347-355.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 20.Benova L, Mohamoud YA, Calvert C, Abu-Raddad LJ. Vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:765-73.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 21.Ades AE, Gordon F, Scott K, et al. Overall Vertical Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus, Transmission Net of Clearance, and Timing of Transmission. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76:905-12.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 22.Gibb DM, Goodall RL, Dunn DT, et al. Mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus: evidence for preventable peripartum transmission. Lancet. 2000;356:904-7.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 23.Indolfi G, Resti M. Perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus infection. J Med Virol. 2009;81:836-43.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 24.Mok J, Pembrey L, Tovo PA, Newell ML. When does mother to child transmission of hepatitis C virus occur? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F156-60.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 25.Ceci O, Margiotta M, Marello F, et al. Vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus in a cohort of 2,447 HIV-seronegative pregnant women: a 24-month prospective study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33:570-5.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 26.Mast EE, Hwang LY, Seto DS, Nolte FS, Nainan OV, Wurtzel H, Alter MJ. Risk factors for perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and the natural history of HCV infection acquired in infancy. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1880-9.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 27.Terrault NA, Levy MT, Cheung KW, Jourdain G. Viral hepatitis and pregnancy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Oct 12. [Online ahead of print][PubMed Abstract] -

- 28.Granovsky MO, Minkoff HL, Tess BH, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in the mothers and infants cohort study. Pediatrics. 1998;102:355-9.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 29.Paccagnini S, Principi N, Massironi E, et al. Perinatal transmission and manifestation of hepatitis C virus infection in a high risk population. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:195-9.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 30.Thomas DL, Villano SA, Riester KA, et al. Perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected mothers. Women and Infants Transmission Study. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1480-8.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 31.Zanetti AR, Tanzi E, Paccagnini S, et al. Mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus. Lombardy Study Group on Vertical HCV Transmission. Lancet. 1995;345:289-91.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 32.Resti M, Azzari C, Galli L, et al. Maternal drug use is a preeminent risk factor for mother-to-child hepatitis C virus transmission: results from a multicenter study of 1372 mother-infant pairs. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:567-72.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 33.European Paediatric Hepatitis C Virus Network. A significant sex--but not elective cesarean section--effect on mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1872-9.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 34.Cottrell EB, Chou R, Wasson N, Rahman B, Guise JM. Reducing risk for mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:109-13.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 35.Rezk M, Omar Z. Deleterious impact of maternal hepatitis-C viral infection on maternal and fetal outcome: a 5-year prospective study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;296:1097-1102.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 36.Hughes BL, Page CM, Kuller JA. Hepatitis C in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Nov;217:B2-B12.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 37.Huang QT, Huang Q, Zhong M, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection is associated with increased risk of preterm birth: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22:1033-42.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 38.Connell LE, Salihu HM, Salemi JL, August EM, Weldeselasse H, Mbah AK. Maternal hepatitis B and hepatitis C carrier status and perinatal outcomes. Liver Int. 2011;31:1163-70.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 39.Hood RB, Miller WC, Shoben A, Harris RE, Norris AH. Maternal Hepatitis C Virus Infection and Adverse Newborn Outcomes in the US. Matern Child Health J. 2023:1343-51.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 40.Puljic A, Salati J, Doss A, Caughey AB. Outcomes of pregnancies complicated by liver cirrhosis, portal hypertension, or esophageal varices. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:506-9.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 41.Tan J, Surti B, Saab S. Pregnancy and cirrhosis. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:1081-91.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 42.Belay T, Woldegiorgis H, Gress T, Rayyan Y. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with concomitant hepatitis C virus infection, Joan C. Edwards SOM, Marshall University. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:372-4.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 43.Wijarnpreecha K, Thongprayoon C, Sanguankeo A, Upala S, Ungprasert P, Cheungpasitporn W. Hepatitis C infection and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41:39-45.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 44.Di Martino V, Lebray P, Myers RP, et al. Progression of liver fibrosis in women infected with hepatitis C: long-term benefit of estrogen exposure. Hepatology. 2004;40:1426-33.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 45.Fontaine H, Nalpas B, Carnot F, Bréchot C, Pol S. Effect of pregnancy on chronic hepatitis C: a case-control study. Lancet. 2000;356:1328-9.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 46.Conte D, Fraquelli M, Prati D, Colucci A, Minola E. Prevalence and clinical course of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and rate of HCV vertical transmission in a cohort of 15,250 pregnant women. Hepatology. 2000;31:751-5.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 47.Hashem M, Jhaveri R, Saleh DA, et al. Spontaneous Viral Load Decline and Subsequent Clearance of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus in Postpartum Women Correlates With Favorable Interleukin-28B Gene Allele. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:999-1005.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 48.Hattori Y, Orito E, Ohno T, et al. Loss of hepatitis C virus RNA after parturition in female patients with chronic HCV infection. J Med Virol. 2003;71:205-11.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 49.Lin HH, Kao JH. Hepatitis C virus load during pregnancy and puerperium. BJOG. 2000;107:1503-6.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 50.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), Hughes BL, Page CM, Kuller JA. Hepatitis C in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:B2-B12.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 51.AASLD-IDSA. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for testing, management, and treating hepatitis C. Unique populations: HCV in pregnancy

- 52.Chappell CA, Scarsi KK, Kirby BJ, et al. Ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir in pregnant women with hepatitis C virus infection: a phase 1 pharmacokinetic study. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1:e200-e208.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 53.Yattoo GN, Shafi SM, Dar GA, et al. Safety and efficacy of treatment for chronic hepatitis C during pregnancy: A prospective observational study in Srinagar, India. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2023;22:134-9.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 54.Chappell CA. Safety, Tolerability, and Outcomes of SofosbuviR/Velpatasvir in Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus during Pregnancy: Interim results from the STORC study. AASLD The Liver Meeting; Abstract 0222. San Diego. Nov 15-19; 2024.

- 55.Freriksen JJM, van Seyen M, Judd A, et al. Review article: direct-acting antivirals for the treatment of HCV during pregnancy and lactation - implications for maternal dosing, foetal exposure, and safety for mother and child. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:738-50.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 56.Kushner T, Lange M, Sperling R, Dieterich D. Treatment of Women With Hepatitis C Diagnosed in Pregnancy: a Co-Located Treatment Approach. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:1454-6.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 57.Chappell CA, Hillier SL, Crowe D, Meyn LA, Bogen DL, Krans EE. Hepatitis C Virus Screening Among Children Exposed During Pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20173273.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 58.Kuncio DE, Newbern EC, Johnson CC, Viner KM. Failure to Test and Identify Perinatally Infected Children Born to Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Women. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:980-5.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 59.Bal A, Petrova A. Single Clinical Practice's Report of Testing Initiation, Antibody Clearance, and Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) in Infants of Chronically HCV-Infected Mothers. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:ofw021.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 60.Hillemanns P, Dannecker C, Kimmig R, Hasbargen U. Obstetric risks and vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus infection in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:543-7.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 61.Polywka S, Pembrey L, Tovo PA, Newell ML. Accuracy of HCV-RNA PCR tests for diagnosis or exclusion of vertically acquired HCV infection. J Med Virol. 2006;78:305-10.[PubMed Abstract] -

Additional References

- AASLD-IDSA. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for testing, management, and treating hepatitis C. Unique populations: HCV in children

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hepatitis C Surveillance 2021. Published August 2023.[CDC] -

- Checa Cabot CA, Stoszek SK, Quarleri J, et al. Mother-to-Child Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Among HIV/HCV-Coinfected Women. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2013;2:126-35.[PubMed Abstract] -

- Honegger JR, Kim S, Price AA, et al. Loss of immune escape mutations during persistent HCV infection in pregnancy enhances replication of vertically transmitted viruses. Nat Med. 2013;19:1529-33.[PubMed Abstract] -

- Jhaveri R, Hashem M, El-Kamary SS, et al. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Vertical Transmission in 12-Month-Old Infants Born to HCV-Infected Women and Assessment of Maternal Risk Factors. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofv089.[PubMed Abstract] -

- Koneru A, Nelson N, Hariri S, et al. Increased Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Detection in Women of Childbearing Age and Potential Risk for Vertical Transmission - United States and Kentucky, 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:705-10.[PubMed Abstract] -

- Kushner T, Chappell CA, Kim AY. Testing for Hepatitis C in Pregnancy: the Time has Come for Routine Rather than Risk-based. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2019;18:206-15.[PubMed Abstract] -

- Money D, Boucoiran I, Wagner E, et al. Obstetrical and neonatal outcomes among women infected with hepatitis C and their infants. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36:785-94.[PubMed Abstract] -

- Plunkett BA, Grobman WA. Routine hepatitis C virus screening in pregnancy: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1153-61.[PubMed Abstract] -

- Polis CB, Shah SN, Johnson KE, Gupta A. Impact of maternal HIV coinfection on the vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1123-31.[PubMed Abstract] -

- Roberts SS, Miller RK, Jones JK, et al. The Ribavirin Pregnancy Registry: Findings after 5 years of enrollment, 2003-2009. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88:551-9.[PubMed Abstract] -

- Tasillo A, Eftekhari Yazdi G, Nolen S, et al. Short-Term Effects and Long-Term Cost-Effectiveness of Universal Hepatitis C Testing in Prenatal Care. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:289-300.[PubMed Abstract] -

- Watts T, Stockman L, Martin J, Guilfoyle S, Vergeront JM. Increased Risk for Mother-to-Infant Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus Among Medicaid Recipients - Wisconsin, 2011-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:1136-1139.[PubMed Abstract] -

- Zeng QL, Yu ZJ, Lv J, et al. Sofosbuvir-based therapy for late pregnant women and infants with severe chronic hepatitis C: A case series study. J Med Virol. 2022;94:4548-53.[PubMed Abstract] -

Figures

Figure 1 (Image Series). Rate of Maternal HCV Infection, by Race/Ethnicity, 2021 — United StatesSource: Ely DM, Gregory ECW. Trends and Characteristics in Maternal Hepatitis C Virus Infection Rates During Pregnancy: United States, 2016–2021. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2023:72(3).

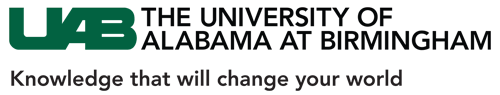

Figure 1 (Image Series). Rate of Maternal HCV Infection, by Race/Ethnicity, 2021 — United StatesSource: Ely DM, Gregory ECW. Trends and Characteristics in Maternal Hepatitis C Virus Infection Rates During Pregnancy: United States, 2016–2021. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2023:72(3). Figure 2. HCV Infection Among Women with Live Births, United States, by Age Group, 2015These data for HCV positive rates are from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Birth Certificate Data in the United States in 2015.Source: Schillie SF, Canary L, Koneru A, et al. Hepatitis C Virus in Women of Childbearing Age, Pregnant Women, and Children. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:633-41.

Figure 2. HCV Infection Among Women with Live Births, United States, by Age Group, 2015These data for HCV positive rates are from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Birth Certificate Data in the United States in 2015.Source: Schillie SF, Canary L, Koneru A, et al. Hepatitis C Virus in Women of Childbearing Age, Pregnant Women, and Children. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:633-41. Figure 3. Anti-HCV among Infants Born to Mothers with HCV Infection: Clearance of Maternal Antibody in Children not Infected with HCVSource: European Paediatric Hepatitis C Virus Network. A significant sex--but not elective cesarean section--effect on mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1872-9.

Figure 3. Anti-HCV among Infants Born to Mothers with HCV Infection: Clearance of Maternal Antibody in Children not Infected with HCVSource: European Paediatric Hepatitis C Virus Network. A significant sex--but not elective cesarean section--effect on mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1872-9. Figure 4. Algorithm for HCV Testing of Perinatally Exposed Children, United States, 2023Source: Panagiotakopoulos L, Sandul AL, Conners EE, Foster MA, Nelson NP, Wester C. CDC Recommendations for Hepatitis C Testing Among Perinatally Exposed Infants and Children - United States, 2023. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2023;72:1-21.

Figure 4. Algorithm for HCV Testing of Perinatally Exposed Children, United States, 2023Source: Panagiotakopoulos L, Sandul AL, Conners EE, Foster MA, Nelson NP, Wester C. CDC Recommendations for Hepatitis C Testing Among Perinatally Exposed Infants and Children - United States, 2023. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2023;72:1-21.Share by e-mail

Check

-On-

Learning

QuestionsThe Check-on-Learning Questions are short and topic related. They are meant to help you stay on track throughout each lesson and check your understanding of key concepts.You must be signed in to customize your interaction with these questions.

- 0%Lesson 2

Since you've received 80% or better on this quiz, you may claim continuing education credit.

You seem to have a popup blocker enabled. If you want to skip this dialog please Always allow popup windows for the online course.

Account Registration Benefits:

- Track your progress on the lessons

- Earn free CNE/CME/CE

- Earn Certificates of Completion

- Access to other free IDEA curricula

Create a free account to get started