Management of a patient who did not complete prior DAA therapy

Clinical Challenge

How would you treat this patient?

Expert Opinions

Oluwaseun Falade-Nwulia, MBBS

Associate Professor of Medicine

Division of Infectious Diseases

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Grant to Institution: AbbVie, Inc.

In this case of a 39-year-old woman who previously completed 4 weeks of treatment with glecaprevir-pibrentasvir, I would consider her oral DAA treatment experienced. In keeping with the AASLD/IDSA guidelines, I would pick a 12-week course of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir-voxilaprevir for retreatment as it gives a 1 pill a day regimen for 12 weeks with high cure rates. In a study of 31 patients who failed glecaprevir-pibrentasvir, 90% of whom had NS5A resistance associated substitutions, 94% achieved SVR 12. (Pearlman et al 2019). In the Polaris 1 and 4 trials, oral DAA treatment experienced patients with HCV genotype 1 infection achieved high SVR rates with (98%) or without (97%) baseline resistance associated substitutions (RAS) prior to retreatment with sofosbuvir-velpatasvir-voxilaprevir. While gelcaprevir-pibrentasvir + sofosbuvir + ribavirin for 16 weeks would be an alternative with cure rates of 96% reported in the MAGELLAN-3 trial of patients who had virologic failure with gelecaprevir-pibrentasvir, this would require the patient to take multiple pills in addition to potential side effects related to ribavirin for a prolonged duration of 16 weeks. I would vote to keep treatment as short and simple as possible. For these reasons, sofosbuvir-velpatasvir-voxilaprevir would be my top choice.

Washington State Department of Corrections

Clinical Associate Professor

University of Washington

Treatment lapses or gaps in treatment are common in the real world. The best approaches to HCV treatment interruptions are not always clear, and there are no evidence-based answers to guide next steps. Therefore, there is no single correct answer for this scenario. Things to take into account when deciding on how to retreat include: 1) how much of the initial course was completed and in what time frame, 2) how much time has passed since the last dose was taken. 3) the severity of underlying liver disease and 4) the likelihood of viral relapse vs. reinfection. In this case, where the patient completed only ≤ 50% of an 8-week course, had a gap in treatment lasting a couple of years, has low level fibrosis, and documented viremia that could represent either viral relapse or re-infection, there are several options for re-treatment: 1) Retreating as a naive patient, since the patient completed 4 weeks or less of a full course of treatment and is not a true failure; 2) Check for HCV resistance and treat based on RAS (although the utility of checking for mutations is not clear); 3) Treat with SOF/VEL/VOX x 12 weeks based on prior treatment experience similar to a g/p failure. Given the lack of data, many experts defer to the more conservative approach and treat with SOF/VEL/VOX x 12 weeks as long as there is not a contraindication. However, in cases of prior partial treatment, due to cost constraints and/or lack of insurance coverage, SOF/VEL/VOX is not always an option. Some clinicians just restart the initial regimen and, anecdotally, most patients have an SVR after completion of the full 8-week treatment course. Of course, the best approach is to avoid gaps in treatment in the first place as best as possible by integrating HCV treatment with treatment for substance use disorder, but this is not always possible or desired by the patient. These cases can often be very nuanced and I would consider discussing with a hepatitis C expert or calling the HCV Clinical Consultation Center (https://nccc.ucsf.edu/clinician-consultation/hepatitis-c-management/) to help make a final decision.

Elbasvir-Grazoprevir Zepatier

Elbasvir-Grazoprevir Zepatier Glecaprevir-Pibrentasvir Mavyret

Glecaprevir-Pibrentasvir Mavyret Ledipasvir-Sofosbuvir Harvoni

Ledipasvir-Sofosbuvir Harvoni Ribavirin Copegus, Rebetol, Ribasphere

Ribavirin Copegus, Rebetol, Ribasphere Sofosbuvir Sovaldi

Sofosbuvir Sovaldi Sofosbuvir-Velpatasvir Epclusa

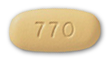

Sofosbuvir-Velpatasvir Epclusa Sofosbuvir-Velpatasvir-Voxilaprevir Vosevi

Sofosbuvir-Velpatasvir-Voxilaprevir Vosevi